Designing aircraft is quite tricky, ones for the navy more so because they insist on using really small runways that move. The aircraft below got at least part way through the design process before someone decided it had been a bit of a mistake to start in the first place and could we just buy something else. Honourable mentions go to the Super Tomcat 21 and the P.1214-3 which would have made the cut but a) seemed too obvious, and b) it’s taken eleven months to write this which puts the article in danger of meeting the same fate as its subjects.

Vought F5U-1

As Task Force 58 approached the Japanese home islands the intensity of aerial attack increased, fortunately the Fleet Carriers had a new weapon in the form of the Vought F5U-1 Flying Pancake. Able to seemingly rise vertically from the deck it could react to pop up raids in a way no conventional aircraft could. With two Twin Wasp radial engines buried in the fuselage the Pancake could rapidly accelerate to over 360mph at sea level, more than fast enough to deal with the Mitsubishi A7M that were her main opponent in the spring of 1946. Also able to carry two 1000lb bombs for strike missions the USN’s only criticism of the F5U was that they couldn’t get enough of them. Part of this enthusiasm no doubt being down to the 40kt approach speed which made carrier landings almost accident free.

Despite the Pancake’s unconventional looks there was sound aerodynamics behind them, trialled on the Vought V-173. Although short fat wings [1] are normally inefficient due to the large tip vortices that are induced, the position and rotation of the propellers worked to cancel them out. This allowed it to be manoeuvrable and structurally strong while also giving it a stall speed that would have Swordfish pilots reaching for the throttle.

The Future we got.

Unfortunately scaling from the V-173 to the XF5U proved more problematic than anticipated. To avoid the aircraft becoming uncontrollable if an engine failed, losing the vortex cancelling prop wash on one side, there was a complex cross-coupling system. This had teething problems while at the same time flight test on the V-173 had led the designers to conclude some form of propeller flapping would be needed. Standard on helicopters to compensate for the changes in lift across the rotor disc this was the edge of the known in 1943 and took some time to incorporate into the larger aircraft. With taxi-tests pushed back until 1947 and a range of jet projects to fund the USN eventually cut funding for the programme, despite the promise of a turbo-prop powered variant able to fly at speeds from 0-475 knots. The strength of the design was however proven when a wrecking ball had to be used to destroy the second prototype.

[1] Low Aspect ratio for the aeronautical professionals.

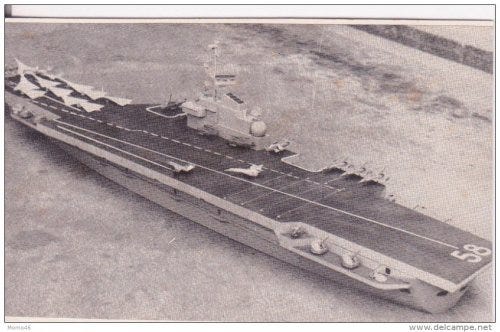

Sturgeon

The Future we were promised.

With the Royal Navy returning to the Pacific the decks of its Audacious and Centaur class carriers bristled with a new reconnaissance and strike aircraft, the Shorts Sturgeon. This packed two 2000hp Merlins, three crew, and a bomb bay capable of holding a 1000lb bomb or four mines, in a package that would fit down a 22’ x 45’ aircraft lift. This was achieved by fitting three bladed contra-rotating props to the engines, as well as reducing the diameter to 10’ allowing them to be parked at an angle that gave an overall width of exactly 20’. That power allowed the Sturgeon Mk1 to hit 348kts at 18,500’ with a rate of climb at 2000’ of over 4000’/min at her max all up mass.

The Sturgeon was a hotrod with the pilot sitting above the leading edge of the wing the prop discs either side of the nose ahead. Faster than the Mitsubishi A7M that had replaced the Zero, long ranged, and fitted with ASV radar the Sturgeon was a step change in the Fleet Air Arm’s strike capability outpacing and outranging the Avengers and Barracudas it had previously used.

The Future we got

Fortunately for everyone involved WW2 finished in 1945, the next year with the speed for which British industry is famed the first Sturgeon Mk1 took flight. With production of the carriers she was intended to operate from suspended and the Mighty Wyvern [2] on the horizon the Royal Navy had no obvious need for the Sturgeon. Despite this 23 were ordered as carrier capable Target Tugs and afflicted with an extended noise for a camera operator to observe airbursts alongside the aircraft. Fortunately for everyone involved, again, this requirement was soon overtaken by the advent of radar laid guns and the small Sturgeon fleet operated as more or less conventional tugs for the rest of their lives.

[2] Or possibly jet aircraft it’s hard to tell.

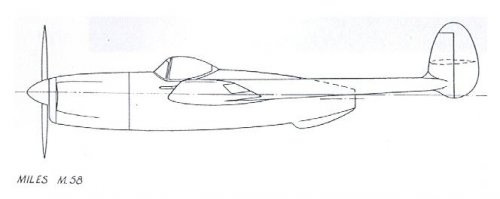

Miles M.58

500 miles south of Japan a flight of M.58s of 1770 NAS maintained a combat air patrol between the ships of Task Force 57 and the Japanese coast. Loitering on the power of their 500hp piston engines Fighter Directors on-board their carriers direct them to unidentified contacts west of their position. Beginning the starting process for the Rolls-Royce Derwent in the aft fuselage the twin boom fighters accelerate towards the bogeys. Within minutes they identify them as six G4M Betty bombers and accelerate through 400 knots to make their attack. Slicing through the Japanese formation the M.58s open up with 20mm cannon, two of the bombers mortally wounded on the first pass trailing smoke and irrevocably descending towards the waters of the Pacific. Within five minutes and two further passes three more Bettys are preparing to ditch while the sixth had turned back towards Japan no longer a threat to the British Pacific Fleet’s carriers.

The M.58 was a mixed power plant fighter designed to cruise efficiently on its 500hp piston engine for up to seven hours with the 2000lbs of thrust from its available when needed for combat. As with the De Havilland Vampire and Venom the twin boom arrangement minimised the thrust lost to the jet pipe and also held the 20mm cannon. The cruising efficiency allowed the M.58 to maintain a combat air patrol for longer and at a much greater distance from the task force than previous naval fighters. Maximising the time and opportunities to intercept enemy aircraft.

The future we got

The M.58 never got beyond a design proposal, not helped by official review of the design concluding the proposed performance wouldn’t be achievable on a 500hp engine. The Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP) presumably thinking the W2/700[3] was in the rear fuselage solely for ballast. In reality 7 hours endurance would probably have been too much for the mid-40s given the comfort levels in a typical single seat fighter of the time, but it would certainly have given the RN options when employing the W.58. Miles also proposed a tandem wing fighter for the navy with a pusher propeller giving excellent deck landing characteristics, having built and flown the prototype without MAP’s permission Miles were castigated and no further official interest was forthcoming. Which was actually fairly cordial for the MAP and Miles relationship.

[3] The Rolls-Royce Derwent was essentially the production version of the Power Jets W2/700 that would likely have been used if the M.58 had entered service.

SNCASO Narval

Despite missing out on a lot of development opportunities during the early 1940s the French aviation industries hit the ground running once the Germans had left. As well as three prototype jet fighters for the Aéronavale it was thought that a piston engine option should also be available. Consequently, SNCASO was commissioned to produce the Narval, a twin-boom Griffon powered strike fighter. With events in Indo-China continuing their two thousand year run of proving empires can’t defeat insurgent warfare, the Narval was soon in action from the deck of the Arromanches, the replacement for the Bearn. With 6 20mm cannon and the ability to carry a 1000kg of bombs the Narval was a step up from the surplus Hellcats and Bearcats that the United States was trying to offload. The subsequent Nene powered Super-Narval saw limited combat over Suez where the extra speed afforded by turbo-jet propulsion kept them safe from inquisitive MiGs of the Egyptian Air Force.

The future we got.

Although the Narval looked like it was the future of aviation in 1946 it suffered from a few minor problems. Unable to get a Griffon, which honestly shouldn’t have been that hard if SNCASO had just bought a surplus Firefly, the two prototypes ended up with French built Jumo 213 knock-offs that suffered cooling issues because a) German engines and b) SNCASO don’t seem to have heard of the Meredith effect and hadn’t scaled the radiator intake appropriately. That however was the least of the Narval’s problems, it took several attempts to even get it airborne with the final fix being to cut a slice out of the tail booms to crank them up another 2 ½ degrees. Once airborne things didn’t get any better, unless you enjoy travel sickness, with a lack of stability in pretty much every axis. Just to make sure, the two prototypes displayed radically different handling issues, with one entering a dive as the flaps were lowered and the other rolling right. At this point the French government did what any sensible person would and cancelled the programme 8 months after the first flight and bought Hellcats.

Douglas D-640

The Future we were promised

Water streamed off the black hull of the USS Grayback as she broke the surface of the South China Sea, moments later the muted sound of a J34 turbojet starting could be heard over the waves crashing. Within 90 seconds the first Douglas D-640 had launched into the breaking dawn and within two minutes the Grayback’s full complement of four were streaking through the skies of North Vietnam as the submarine descended back beneath the waves.

Conceived as a means of accurately delivering a nuclear weapon without warning the D-640 was a remarkably small aircraft at 32’ 11” long, fitting into the same footprint as a Regulus missile. Unlike a Regulus missile the D-640 didn’t require radio control by surface ships to find its target. A concept that at least partially defeated the purpose of a submarine launched deterrent. As the Cold War remained tepid the USN found the 640 also excelled as a conventional attack aircraft allowing them to strike from unexpected directions. Over Vietnam the diminutive Douglas would be employed conducting precision strikes on high value targets while large USAF and USN strike packages carried out decoy raids to draw away the defences.

The Future we Got

The USN lost interest in submarine-based aircraft fairly quickly once it became obvious they could just launch ballistic and cruise missiles accurately enough for a nuclear warhead to work. This also had the advantage of not needlessly exposing submariners to fast jet pilot’s egos. There are also a lot of problems basing aircraft on a ship who’s unique selling point is hiding. Firstly, launching the aircraft can’t help but narrow down the opposition’s search area. This in turn reduces the amount of sorties it’s sensible to launch, which will affect the competence of the whole operation. Much like getting to Carnegie Hall, becoming a fully swept up squadron takes practice. Which leads us to another problem, you can’t get a squadron of aircraft on a submarine. Four would probably be pushing it. Which on a good day might get you two serviceable ones, except you won’t know for sure until the submarine is at its most vulnerable, wallowing around on the surface. At which point it’s not really clear what the point is. An opposition you’d send two jets against probably aren’t worth the expensive of a SSV [4], and one who is worth its expensive aren’t going to be bothered by a couple of aircraft showing up.

So, the D-640, a technological dead end and a waste of design office time? Well yes, and at the same time no if you find yourself proposing a light attack aircraft capable of carrying a nuclear bomb from the deck of an actual aircraft carrier. Heck with that kind of experience to fall back on it might end up being the most widely operated conventional carrier jet ever.

[4] SS – Submarine, V – Primary armament heavier than air aircraft. Incidentally the C in CV is for Cruiser fact fans.

Super Venom

The Future we were promised.

Afterburners illuminating their rear fuselage two De Havilland Super Venoms sped through the twilight skies over Egypt early on November 1st 1956. Losing altitude as they approached their target the aircraft from 809 Naval Air Squadron embarked in HMS Albion dropped below Mach 1 as the air thickened. Crossing a ragged wire fence in the sand that marked the boundary of Almaza airfield the Super Venom’s crews identified their targets and opened up with a volley of 60lb rockets, followed by 20mm cannon fire ripping into a parked flight of MiG-15 fighters. As the pair of fighters from 809 departed the scene towards the coast Sea Hawks from 800 NAS began a follow-up attack while clouds of dark smoke rose into the air.

The Super Venom was proposed in 1952 to meet the requirement for an all-weather fighter after the Royal Navy had pulled out of the increasingly confused blob of programmes that included N14/49, F4/48, and various strike and reconnaissance aircraft. De Havilland took the Sea Venom that was then flying in prototype form and removed everything aft of the cockpit. To this it added a swept wing, T-tail, and conventional fuselage housing an afterburning Rolls-Royce Avon Mk201 with 9,500 lbs of thrust. With a sea level max speed of Mach 0.975 it could easily break the sound barrier at altitude becoming the RN’s first supersonic fighter. Entering service with 809NAS just in time to see service during the Suez Crisis later developments would add Firestreak air to air missiles to the Super Venoms armoury while engine upgrades would just about allow performance to keep pace with the added weight of additional systems and external fuel tanks.

The Future we got.

After ordering two prototype Super Venoms in the January of 1952 the Fifth Sea Lord [5] must have been slightly disappointed to receive a letter from De Havilland’s chief designer in November of that year saying that due to a lack of design staff and other commitments they wouldn’t actually be able to deliver any. In what could be consider a gutsy move he then went on to suggest the navy might be interested in going back to a navalised DH.110 variant, only two months after it had a made a big impact at the Farnborough Air Show. Literally and figuratively. His hand somewhat forced by the lack of other options Fifth agreed to this and the RN would eventually get the Sea Vixen about 18 months before the USN got the Phantom, an aircraft whose performance was so good it was still the best choice when the Vixen needed replacing a decade later.

[5] Certainly a better title for the head of the Fleet Air Arm than the modern one of Director Force Generation.

Mirage IV M

With deltas being the design of choice for the fabulous fifties it was no surprise when the Aéronavale selected a version of the Mirage IV for its Verdun class carrier. Rather than the nuclear strike role however the IV M was optimised for the air defence of the French fleet, as such the navigator’s cockpit was removed allowing the overall length to be reduced by around 4m with a folding nose allowing the length to reduce further for stowage in the hangar. At the same time the engines were moved forwards reducing the fuselage aft of the trailing edge of the delta. This remained the same area and basic configuration as on the IV A. Revised undercarriage gave the IV M a higher angle of attack on the ground to improve catapult take-off performance.

Entering service in the early sixties the IV M’s performance was outstanding, able to reach 36,000’ in under two minutes of launching from the Verdun. With their 67,000’ ceiling Aéronavale pilots were soon boasting of their ability to intercept RAF Lightnings from above, France’s withdrawal from NATO’s integrated command in 1966 coming as something of a relief as it at least reduced the opportunities for it to happen.

The Future we got

Although the Mirage IV M promised outstanding performance in an attractive package, the Marie Marvingt of aircraft if you will, it was also a bit too large to fit on the Clemenceau class carriers. Broadly the same length and width as a Phantom, if a bit lighter, it would have been sporty operating from the smaller ships.

Unfortunately, the roughly twice as large Verdun was cancelled in 1961 due to costs and the world was denied an attractive French naval aircraft until the arrival of the Rafale. No the Étendard doesn’t count.

Crusader III

The Future we were promised

The Crusader III took everything that was good about the Crusader I & II and turned it up to 11. Chin intake, bigger and jutting forward like an attacking shark’s mouth to control the airflow as it neared Mach 3. Ventral strakes, so big they had to fold to the sides when the undercarriage was lowered so they wouldn’t break off on the ground. Weapons, why not add three Sparrows to the four Sidewinders and 20mm cannon. Range, speed and maximum altitude were all significantly increased while retaining the legacy Crusader’s manoeuvrability.

In the skies of Vietnam, the Super Crusader was virtually unbeatable able to manoeuvre with the Vietnamese Air Force’s MiGs while being able to use it’s speed and acceleration to disengage at will. Even USAF strike packages admitted to preferring a USN escort when going downtown. Post war the F8U3 would put its high-altitude performance to good use over the North Atlantic providing long range CAP. Allowing them to intercept Soviet Tu-95s before they came in radar range of the carrier battle group. A last hurrah would come with Operation Desert Storm where the final USN Crusader squadron, VF-191 ‘Satan’s Kittens’, achieved two kills during the first day of combat operations.

Support The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes: Volume 3 here

The Future we Got

Despite outflying the competing F4H the F8U had a few short comings that its bullet like speed couldn’t overcome. Although both aircraft carried the Sparrow radar guided missile the Phantom had a second crew member who could devote his time to operating it. The Crusader pilot meanwhile had to do the equivalent of texting and driving to use the weapon. The Phantom also had a useful air-to-ground capability something never intended for the Super Crusader and which counted against it taking up space on a carrier deck. Experience of the early jets had also put most naval pilots off the idea of single engined aircraft giving McDonnell Douglas’ contender another advantage. Too specialised for the USN the five F8U3s would see out their lives with NASA, who were soon asked to stop using them to intercept Phantoms because it was getting embarrassing.

DH.127

The future we were promised

As the South Atlantic spray swept across HMS Queen Elizabeth's deck the first of six DH 127s rolled down the deck its twin Speys' afterburners illuminating the early morning. Approaching the deck edge the two RB.162 lift engines forward of the cockpit ran up to full power lifting the nose allowing the DH 127 to complete a free take-off from the carrier. Accelerating through the sound barrier the first two delta winged aircraft were armed with four Red Top missiles, below them the remaining DH.127s carried eight 1000lb bombs intended for the airfield at Port Stanley. Having entered service in the early 1970s the DH.127 was a tailless delta designed to fulfil the RN’s need for a supersonic aircraft able to operate in strike and air defence rolls. Although there had been some teething snags the STOL capabilities had allowed the navy to procure aircraft carriers without the expense and complexity of catapult equipment. With semi-recessed carriage possible for a range of weapons the de Havilland Delta could reach Mach 2.5 at altitude or Mach 0.9 at sea level.

This speed allowed the four strike aircraft to catch the Argentinian defenders completely unawares, littering the runway with bombs. The two air defenders meanwhile had a brief, one-sided, engagement with two Mirage IIIs to the north of the islands.

Returning to the carrier the DH.127s vectored the thrust from their Speys diverting it through a vectoring nozzle forward of the afterburner. Combined with the thrust from the lift engines the aircraft were able to slow to 85 knots, combined with the wind and ship’s speed the aircraft approached the deck at barely 50 knots. This gave the tail hook and arresting gear a much easier job, again reducing the cost of the carriers. All six aircraft landed safely, the only damage being a hole in the tail of one of them, gained over Port Stanley.

The Future we got

Despite a number of promising design proposals for the RN’s OR.346 requirement it was decided the Navy and RAF should combine their not that similar needs for a VSTOL strike aircraft. The former wanting a two seat interceptor with a strike capability, the latter a single seat attack aircraft with a reconnaissance capability. The resulting P.1154 being a just about acceptable compromise for a few months until it was slowly realised that it wouldn’t work for the Navy, who ordered Phantoms in 1964. All that remained was for the incoming Labour government to cancel the rest of the P.1154 project, along with the TSR.2, and generations of British aviation enthusiasts could make claims about underhand dealings by the US military-industrial complex. Rather than just admitting the MoD has never been good at project management.

A-12 Avenger

The uranium enrichment plant lay in the base of a long dormant volcano, surrounded by a ring of snow-covered peaks. The surrounding area was defended by a veritable forest of surface-to-air missiles, while a nearby airbase held Fifth generation fighters at readiness alongside a squadron of F-14s, a legacy from a previous regime’s closer relations with the USA. Despite these rings of layered defence, a little after 0945Z the first of a series of 500lb laser-guided bombs took out the ventilation shaft above the enrichment plant before follow up weapons destroyed the facility itself.

The response was notable mainly for not happening, at no point could any aircraft be detected. Scrambled Fifth generation fighters searched the sky in vain. The only evidence that pointed to the destruction being caused by an enemy attack was a few seconds of CCTV camera footage that showed a seeker head penetrating the main enrichment hall before the signal was cut-off.

Meanwhile at 1100Z an A-12 of VA-75 landed back on the deck of the USS Nimitz as it cruised the waters of the Gulf of Oman. The triangular replacement for the legendary A-6 Intruder was as close as you could get to a naval B-2 with the RADAR signature of a small bird and a similarly minimal IR one, with effective mission planning it could penetrate a foreign country’s air defences, destroy its target, and return without them ever knowing. Even in a GPS jammed environment.

The Future we got

The A-12 suffered from entering development just as the high of Reagan era defence spending was coming to an end. Which was unfortunate given that by 1990, two years after McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics had been awarded the contract, the aircraft was 30% over its target weight and the radar system was proving impossible to get working. With the A-12 programme promising to consume almost three quarters of NAVAIR’s budget for new aircraft cancellation became inevitable. Which would normally be the end of the story, but a series of lawsuits would carry on until 2014 to decide who owed who what, with the final decision being that Boeing (having absorbed McDonnell Douglas) and General Dynamics should each return $200 million to the USN. Despite being 30 years after the initial contracts had been issued for concept designs this depressingly probably isn’t even a record for a defence programme that failed to deliver anything.

Bing Chandler is a former Lynx Observer who is recovering from the trauma of being expelled from Red Bubble. He now has a Zazzle store instead.

Thank you for reading the Hush-Kit site. It’s all been a huge labour of love that I have devoted a great deal of time to over the last 12 years. There are over 1100 totally free articles on Hush-Kit, think of the work that’s gone into that! To keep this going please do consider a donation (see button on top of page) or by supporting on Patreon. Not having a sponsor or paid content keeps this free, unbiased (other than to the Whirlwind) and a lot naughtier. We can only do this with your support. I really love this site and want it to keep going, this is where you come in.

To those who already support us I’d like to say a big thank you.

All the best

Hush-Kit