What Artist Francis Bacon Has In Common With The Fairey Gannet

(I think I've been watching too many Adam Curtis documentaries)

At first glance, the Irish-British artist Francis Bacon and the Fairey Gannet—an ungainly Cold War-era anti-submarine aircraft—seem worlds apart. One redefined figurative painting through violence, distortion, and raw psychological force. The other patrolled North Atlantic skies like a weird fat bastard of doom with a bark like a chainsaw. But look a little closer, and surprising affinities emerge.

Both are icons of postwar Britain—strange, brutal, and unforgettable. One haunted galleries, the other hung over grey oceans. And both, in their own way, embody a certain national talent for turning the grotesque into something deeply compelling (see Noel Edmonds for details).

Let’s start with the obvious: neither was conventionally beautiful. Francis Bacon’s paintings are, like the last one-night stand you had, a nightmarish collision of meat, space, and anguish. The Fairey Gannet appears to have been designed in a mad weekend when Hieronymus Bosch, Terry Gilliam, and Heath Robinson locked themselves in a remote cottage, took laudanum, and tried to scare each other.

Short-legged, big-bellied, with a folding double-hinged wing that defies aerodynamics and reason, it is both hideous and beautiful; it’s a flying contradiction. And yet, both Bacon and the Gannet confront you with forms you can’t ignore. They demand a second look—not because they please the eye, but because they disturb it. Both refuse prettiness and reward attention with impact.

Francis Bacon was born in Dublin—then still part of the United Kingdom—in 1909, just six years before the Fairey Aviation Company was founded. Ireland would later gain independence, and its Air Corps went on to operate Fairey aircraft, including a single Fairey IIIF Mk II acquired in 1928 (which crashed in 1934) and a Fairey Battle that landed in Ireland after becoming lost during a training flight.

Fairey Aviation began modestly, operating from a single room in Piccadilly, London—just two miles from where Bacon would later establish his iconic South Kensington studio. In 1949, the year the Fairey Gannet made its maiden flight, Bacon debuted his first major solo exhibition at the Hanover Gallery, featuring a series of six haunting "Head" paintings.

That year marked a pivotal moment for both the artist and the aircraft: the Gannet launched into the freshly chilly Cold War skies, and Bacon emerged as one of Britain’s most significant postwar painters. Each, in their own field, embodied a new and unsettling vision of the modern world.

Functionally ugly

Then there’s their shared obsession with function over elegance. Bacon painted not to soothe, but to expose. He wanted to trap reality in its most violent moment, as he put it—flesh and psyche under pressure. The Gannet, meanwhile, wasn’t built to win beauty contests but to save ships from Soviet submarines. Its unusual double-Mamba turboprop engine arrangement—two engines driving counter-rotating propellers through a single gearbox—was the aviation equivalent of Bacon’s twisted figures: grotesque, yes, but technically brilliant. Like Bacon’s art, the Gannet’s design had purpose under the ugliness.

Both also represent anxiety made manifest. Bacon’s canvases pulse with dread—screaming popes, contorted lovers, anonymous meat figures pinned like specimens. His work is soaked in terror. The Gannet, meanwhile, existed to act on dread. It was a Cold War sentinel, sniffing out Soviet submarines in the grey fear between nuclear silence and catastrophe. Its very presence spluttering and snarling over the waves was a reminder that Armageddon might just be lurking under the surface. Bacon painted that psychological pressure; the Gannet flew through it. Both are driven by the mystique de la Merde, the appeal of the unseemly, be it a forbidden tormented carnality or an attraction to obliterating submarines.

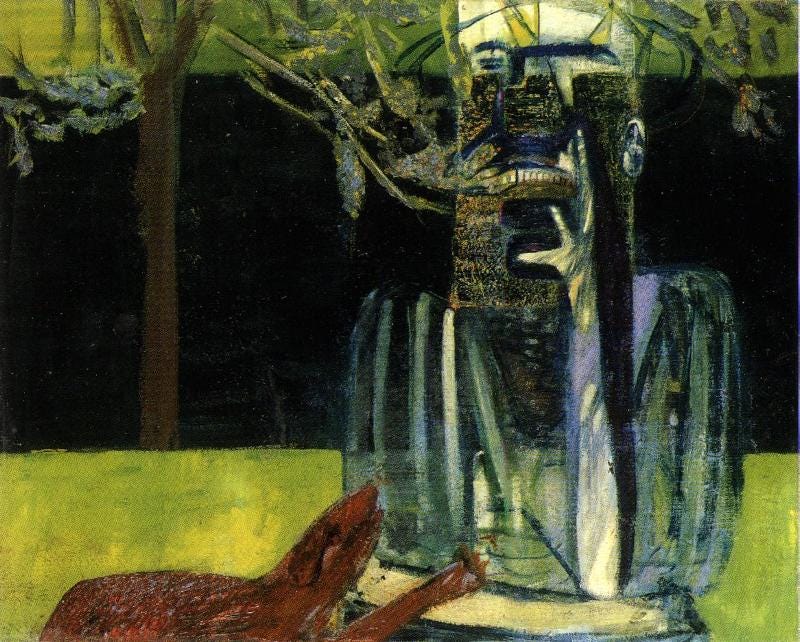

Though very much 1950s animals, they both have their conceptual genesis in the 1930s. In 1935, one Captain Archibald Graham Forsyth proposed a ‘double engine’ carrier aircraft. According to Putnam’s Fairey history, this consisted of, “two twelve-cylinder vertically-opposed engines sharing a common crankcase, but with separate crankshafts driving contra-rotating propellers..to provide the power and many safety advantages of a twin without the associated handling, wing-folding and shipboard accommodation difficulties.” In the same period, Bacon would paint The Crucifixion and Figures in a Garden (also known as Seated Figure, The Fox and the Grapes, and Goering and his Lion Cub).

Of course, both Bacon and the Gannet are also products of British postwar pragmatism. After the Second World War, Britain could no longer afford the grandeur of American optimism or the ideological swagger of Soviet modernism. Instead, it bred things that were tough, idiosyncratic, and slightly haunted. Like Noel Edmonds, who was born a year before the Gannet.

Bacon’s paintings don’t offer utopia or clarity—they flay open the human condition with brutal honesty. The Gannet doesn’t soar like a Spitfire; it grumbles and folds, like the weary realism of a country managing decline with duty and awkward tired brilliance.

There’s a strangely appropriate soundtrack connection, too. The Gannet was famous—or infamous—for the sound of its contra-rotating propellers. Ground crews joked that it didn’t so much fly as shout at the sky. It had a guttural, grinding, almost industrial noise that echoed over the airfields of Northern Europe. In a way, that mechanical screeching is the perfect audio accompaniment to a Bacon triptych. Imagine staring at Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X while a Gannet idles just off-canvas. There’s your sonic nightmare.

Even in terms of career trajectory, they oddly align. Bacon was dismissed by some critics early on as a purveyor of gore and chaos, just as the Gannet was mocked for its looks and unconventional features. But over time, both earned respect not just for what they did, but for how uncompromisingly they did it. Bacon never softened his vision. The Gannet never pretended to be something it wasn’t. They stuck to their briefs—Bacon to emotional evisceration, the Gannet to sub-killing vigilance. Both outlived their detractors.

Let’s not overlook the mutual fascination with folding structures. The Gannet had famously complex folding wings—designed to squeeze its bulky frame into Royal Navy carriers. Bacon, meanwhile, often folded space and anatomy into claustrophobic interiors. His rooms seem to compress around the subject, as if the walls themselves are anxious. The Gannet folded physically; Bacon folded conceptually. Both created tension through collapse.

There’s also something to be said for their unexpected humour, or at least irony. Bacon insisted he wasn’t a morbid painter, just an honest one. His work, for all its horror, has a black wit—a theatricality verging on the absurd. Similarly, the Gannet, while deadly serious in purpose, looks like a scrapheap that got its shit together and flew away. It’s hard not to smile when you see one, especially mid-fold. Both manage to disturb and amuse in the same breath.

And then there’s the matter of endings. Bacon died in Madrid in 1992, still painting, still unnerving. The Gannet was retired from frontline service in the 1970s, replaced by the rather maternal Wessex helicopter. But both left legacies that outlasted their active years. Bacon remains one of the most influential painters of the 20th century, his canvases haunting museums and market records alike. The Gannet lives on in airshows and enthusiast communities, celebrated now for the same strangeness that once earned it mockery.

In the end, Bacon and the Gannet share something deeper than nationality or era. They both prompt you to confront the discomfort at the intersection of function and form. Bacon never gave you what you wanted—he gave you what you felt. The Gannet did a job few others could, in conditions few others dared. They each, in their own language, embodied the raw, utilitarian poetry of survival.

So the next time you're standing before a Bacon painting, feeling the hum of dread behind the brushstrokes, spare a thought for the Fairey Gannet. Somewhere, once, it too screamed, doing something ugly, important, and entirely unforgettable. In its way, it was a Bacon on wings.

Death and destruction

Francis Bacon's lover, George Dyer, died by suicide on October 24, 1971. He was found dead in a hotel bathroom in Paris, just two days before the opening of Bacon's major retrospective at the Grand Palais. This devastating event was sandwiched between two Gannet crashes, the fatal crash of 6 May 1970 Fairey Gannet AEW.3 XR433 near Yeovilton, Somerset and XL474 on 29 Jun 1972 in Ilchester, Somerset.

Contra Culture

Francis Bacon’s use of circles—often ghostly, incomplete, or cage-like—serves to isolate his subjects psychologically, not physically. These ovals and loops create tension, enclosing figures in metaphysical spaces without ever truly containing them. They are theatrical, like spotlights, yet confining, like surgical arenas. Bacon’s circles are never ornamental; they heighten anxiety, emphasising that the subject cannot escape scrutiny—or itself.

The contra-rotating propellers of the Fairey Gannet, on the other hand, are very much physical. They spin in opposite directions, eliminating torque and stabilising flight, but in doing so, they become a hypnotic visual echo—one disc inside another, endlessly in motion. Mechanically efficient, yet visually unsettling.

What connects them is this circular motif as disorientation. Bacon’s circles unmoor the figure from reality, much as the Gannet’s spinning blades obscure the sense of forward motion. Both are functional within their domains—Bacon’s to intensify emotion, the Gannet’s to stabilise flight—but each produces a kind of surreal effect. Circles that don’t soothe or complete, but spin or trap.

Where Bacon uses circles to collapse space around the subject, the Gannet’s propellers disrupt space ahead of it. Both are rotating boundaries—symbols of power, but also of confinement, of control edging into chaos.

West Germany

The Gannet also served with the West German Marineflieger. Bacon’s paintings, often featuring distorted human figures and bleak interiors, mirrored the existential anxiety and psychological tension present in West German society as it reckoned with its Nazi past and sought a new identity. His exhibitions in West Germany, notably in cities like Berlin and Munich, were met with critical acclaim. German collectors and museums demonstrated a strong interest in his work, and he was featured in several major retrospectives and exhibitions, particularly during the 1970s and 1980s. Intellectually, Bacon’s emphasis on the brutality of existence aligned with German existential and post-war philosophical thought, including thinkers like Nietzsche and Heidegger. While Bacon himself was apolitical and resisted ideological interpretations of his work, the emotional depth and moral ambiguity of his art made a profound impact in West Germany, where audiences were particularly attuned to the darker aspects of the human condition, much like the Gannet.

Australia

Australia connects to both the Fairey Gannet and Francis Bacon in unexpected, resonant ways. The Royal Australian Navy operated the Gannet in the 1950s and ’60s, its folded silhouette prowling the Pacific as a Cold War sentinel. Meanwhile, Bacon’s raw, visceral art has long found a captive audience in Australia’s art scene, influencing painters like Brett Whiteley. Both the Gannet and Bacon’s work speaks to an isolated tension—mechanical or psychological—mirrored in Australia’s own cultural landscape: distant, intense, scrutinising. In the outback or the gallery, that mix of isolation, power, and existential pressure binds the machine and the man alike.

Indonesia

Indonesia links to both the Fairey Gannet and Francis Bacon through echoes of postcolonial tension, control, and transformation. The Indonesian Navy briefly operated Gannets—symbols of imported military power, adapting to regional realities. Meanwhile, Bacon’s themes of fractured identity, containment, and trauma resonate in a country shaped by abrupt shifts—from colonialism to independence to authoritarianism. His distorted figures could mirror the psychological contortions of a nation in the process of reinventing itself. Both Gannet's and Bacon’s art embodies foreign forms forced into new contexts—mechanical or emotional—highlighting the uneasy friction between legacy and autonomy in Indonesia’s mid-century narrative. Each reveals beauty amid turbulence.

The King and I

On October 18th, 1972, Prince Charles flew in two Fairey Gannets from RNAS Yeovilton—AEW.3 XL500 and trainer T.5 XG889, which he landed himself from the centre cockpit. Both flights, piloted by Lt Cdr Tim Goetz, marked his only experience in the strange, grumbling aircraft. That day cemented his patronage of the Gannet AEW.3 project. But beyond nostalgia, the moment resonates as a late imperial echo: a future king in a fading machine of empire, flying above a limping Britain reeling from retreat.

Francis Bacon, painting in those same years, captured this national disintegration with flayed figures and psychological dread. Where Charles embodied tradition under pressure, Bacon exposed its collapse. Both, in their way, lived through the theatre of post-imperial identity—one flying the dying tools of empire, the other portraying its internal unravelling. The Gannet, with its utilitarian brutality, becomes the perfect symbol: an aircraft of purpose without grace, flown by a prince into a future already folding.

Haunted Gannet Bacon

Together, Charles, Bacon, and the Gannet chart the haunted postwar transition—from projection to introspection, from empire to anxiety. One in the cockpit, one on canvas, both navigating the turbulence of what Britain was—and what it was no longer allowed to be.

The Fairey Gannet’s propulsion system—two turboprop engines driving a single shaft with contra-rotating propellers—is a marvel of complexity concealed in apparent clumsiness. It solved practical challenges with an unorthodox elegance, prioritising function over form. Similarly, Francis Bacon’s choice of medium—oil on canvas, often violently applied with rags, brushes, and even bare hands—was a visceral, layered engine for emotional intensity. Both systems are less about smooth refinement and more about controlled turbulence.

Just as the Gannet’s twin engines fed into one gearbox to stabilise flight, Bacon’s chaotic techniques fed into a unified, unforgettable image. Each allowed turbulence within a structure—an embrace of violent energy channelled into clarity. Neither sought beauty in a classical sense; both found it in disturbance.

The Gannet’s propulsion wasn’t just innovative—it was symbolic of pressure held in balance. Bacon’s medium functioned the same way: thick, smeared oils forming images on the brink of collapse. Propulsion and pigment, both complex, industrial, and faintly grotesque, become unlikely vessels of profound expression. Much like Noel Edmonds.

Brilliantly bonkers. Cheered me right up. I must try to be more Double Mamba in my everyday life.

Utterly insane and spectacular. And brilliant.

I mean this post, of course. As well as the Gannet and Bacon.

Only on Hush-Kit could this possibly appear.

I can't wait for when you decide to compare the two contemporary "Hustlers;" the one from Convair and the other from Larry Flynt. A purely American riposte to your purely British opening salvo.

You're welcome. :-)